Roy Lichtenstein. The master of American Pop Art.

ArtWizard, 24.06.2019

"I'm never drawing the object itself. I'm only drawing a depiction of the object - a kind of crystallised symbol of it."

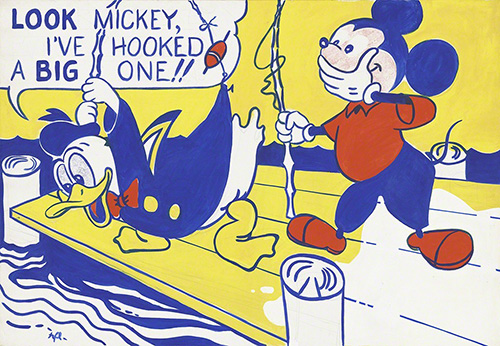

Roy Lichtenstein was one of the emblematic pop artists of the 20th century on the American art market and globally. When he painted his work Look Mickey, in the early 60s, this was the starting point in his career. At the time, the style commonly used was expressionism and the so called “commercial art” was not presented into galleries. This marked a major shift away from abstract expressionism, whose often tragic themes were thought to well up from the souls of the artists, however this was the predominant style at the time. Lichtenstein's inspirations came from the commercial culture at large and suggested little of the artist's individual feelings.

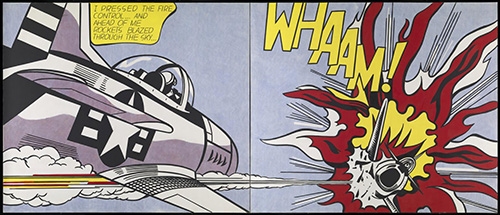

What Lichtenstein did was to stress on the way it works looked – as if they have been part of some comics or advertisement materials, as he painted them with flat colours and using paint and stencils.

He took his inspiration from the everyday images of the advertisement and cartoons in the newspapers, but later in his career his was influenced also by the works of Monet and Picasso. With his “commercial art like” works, Lichtenstein became the leader of the new art movement, the American Pop Art, along with Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. One of the special features of his works was that they documented, while parodied, some everyday subjects that were interesting for Lichtenstein, very often in a tongue-in cheek manner. One of the main galleries that exhibited his early works was the New York Gallery “Leo Castelli”.

At first, Lichtenstein was widely criticised, however this is how he acquired wider recognition. His style was greatly accused in banality, lack of originality and even copying.

Despite of such criticism, his iconic images have become synonymous of Pop Art and his way of creating his works, which combined some ways of mechanical reproduction and hand drawing has become critical for the significance of this new at the time art movement. Lichtenstein was very much into mechanical reproduction and used the so called “Ben-Day dots”, that became significant for one of the main features of the Pop Art, proving his belief that in Pop Art, all messages or forms of communication are filtered by code or language.

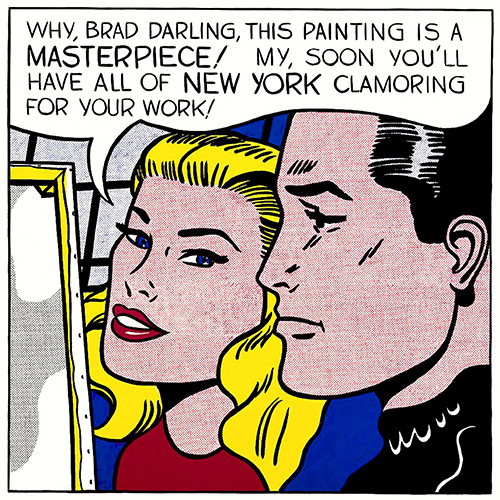

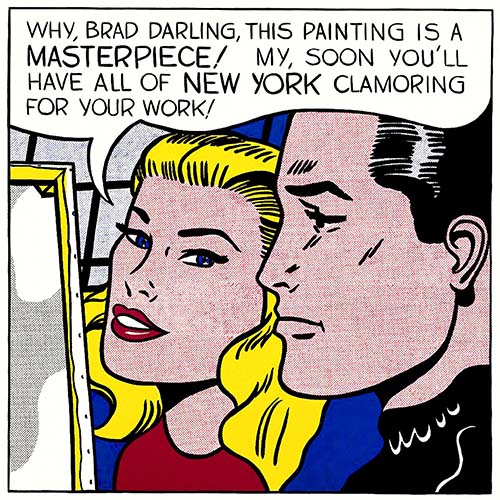

In terms of what was his most influential work, we can say that Look Mickey and Drowning Girl have the lead. The most expensive work however is called Masterpiece, sold for USD 165 million in January 2017, becoming one of the fifteen most expensive paintings ever sold. The story around this sale is quite curious, as the New York Times confirms the sale to be performed by Agnes Gund, an American arts patron, reportedly to the hedge fund manager, billionaire and art collector Steve Cohen “for a specific purpose: to create a fund that supports criminal justice reform and seeks to reduce mass incarceration in the United States.”

Although, in the early 1960s, Lichtenstein was often casually accused of merely copying his pictures from cartoons, his method involved some considerable alteration of the source images. The extent of those changes, and the artist's rationale for introducing them, has long been central to discussions of his work, as it seemed to indicate whether he was interested above all in producing pleasing, artistic compositions, or in shocking his viewers with the garish impact of popular culture.

What is interesting about Roy Lichtenstein is that he copied the source image by hand, alter the image as to suits his visions and then trace this altered image onto a canvas, using a projector. In this entirely manual process, he would stress on the Ben-Day dots, exaggerating on the dot pattering as it was used in printing commercial or advertising images.

His transformations of the source image typically included reducing the colour used palette to saturated primary colours, heightening contrasts, and “emphasising the pictorial clichés and graphic codes of commercially printed imagery.” In Drowning Girl, for example, Lichtenstein cropped out much of the original scene and modified the statement in the text bubble, amplifying this image of a damsel in distress.

Throughout his career, Lichtenstein confounded such oppositions—between reality and artificiality, high art and mass culture, abstraction and figuration, and the manual and mechanical—to reveal their interdependence.

Although being inspired by the commercial culture, he was an avid jazz fan, often attending concerts at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. He frequently drew portraits of the musicians playing their instruments, in his own unique style.