Marie Bracquemond, the shadowed yet bright Impressionist painter

ArtWizard 01.06.2020

"Impressionism has produced ... not only a new, but a very useful way of looking at things. It is as though all at once a window opens and the sun and air enter your house in torrents".

An underdog of the Impressionist scene, and a far-cry from Cassatt and Morisot’s affluent and privileged upbringing, Marie Bracquemond beat the odds. Her working-class family meant she was unable to follow a formal art training like her contemporaries, and was therefore predominantly self-taught. However, when Neoclassical painter, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, saw Bracquemond’s work, her success was forecast. Bracquemond didn’t remain under Dominque-Ingres’ watchful gaze for long though, as he disapproved of her wandering curiosity wanting to paint anything other than “flowers, fruit [or] natures-mortes.”

The artist was born Marie Anne Caroline Quivoron on December 1, 1840 in Argenton-en-Landunvez, near Brest, Brittany. She did not enjoy the same upbringing or career as the other well-known female Impressionist – Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot and Eva Gonzalès. She was the child of an unhappy arranged marriage. Her father, a sea captain, died shortly after her birth. Her mother quickly remarried to a M. Pasquiou, and thereafter they led an unsettled existence, moving from Brittany to the Jura, to Switzerland, and to the Auvergne, before settling in Étampes, south of Paris. She had one sister, Louise, born while her family lived at Corrèze, near Ussel, in the Auvergne, in the ancient abbey of Bonnes-Aigues.

,_1880.jpg)

Marie Bracquemond, La Dame a l'Eventail (Self-portrait in a Spanish Costume), 1880

She began lessons in painting in her teens under the instruction of M. Wasser, "an old painter who now restored paintings and gave lessons to the young women of the town". She progressed to such an extent that in 1857 she submitted a painting of her mother, sister and old teacher posed in the studio to the Salon which was accepted. She was then introduced to Ingres who advised her and introduced her to two of his students, Flandrin and Signol. The critic Philippe Burty referred to her as "one of the most intelligent pupils in Ingres "studio". She later left Ingres' studio and began receiving commissions for her work, including one from the court of Empress Eugenie for a painting of Cervantes in prison. This evidently pleased, because she was then asked by the Count de Nieuwerkerke, the director-general of French museums, to make important copies in the Louvre.

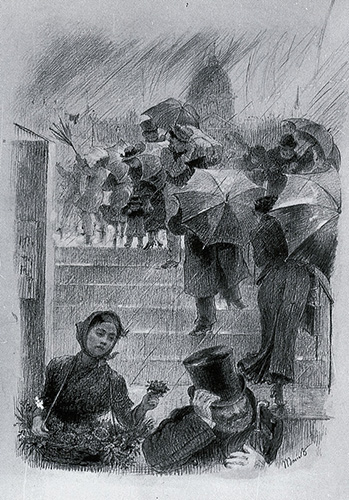

Marie Bracquemond, The Umbrellas, 1882

It was while she was copying Old Masters in the Louvre that she was seen by Félix Bracquemond who fell in love with her. His friend, the critic Eugène Montrosier, arranged an introduction and from then, she and Félix were inseparable. They were engaged for two years before they married in 1869, despite her mother's opposition. In 1870 they had their only child, Pierre. Because of the scarcity of good medical care during the War of 1870 and the Paris Commune, Bracquemond's already delicate health deteriorated after her son's birth. Much of what is known of Bracquemond's personal life comes from an unpublished short biography authored by her son entitled "La Vie de Félix et Marie Bracquemond".

Braquemond’s large impressions of women en plein air capture her vivacious style and vibrant colour palette, as she celebrated the modern woman through her paint brush. Despite being referred to as one of "les Trois Grandes Dames" (the three great ladies – along with Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt) of the Impressionist movement by the famous French art historian, Henri Focillon in 1928, the work of Marie Bracquemond was somewhat obscure until at least the 1980s. A good deal of what we know about her comes from the brief biography that Pierre, her only child, wrote about his artist parents. In contrast, it was her husband, the evidently domineering Felix who resented her career and loathed the Impressionist style, who played a significant role in downplaying the importance of Marie Bracquemond in the larger context of the Impressionist movement.

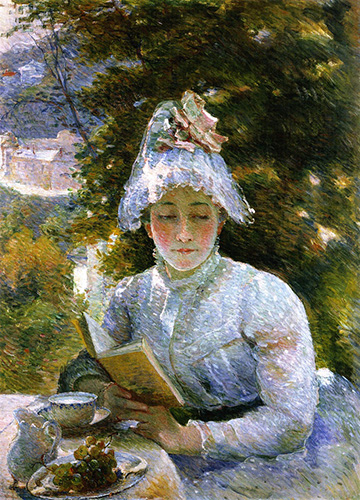

Marie Bracquemond, Afternoon Tea, 1880

Nevertheless, the artist persisted in developing her apparently prodigious talent, incorporating en plein air painting techniques of her youth into her professional regimen while working with some of the most notable artists of the period such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas and, later on, Paul Gauguin. Gradually, Bracquemond established her own distinctive, colorful approach to the style and she was rewarded with invitations to exhibit her work, including at the Impressionist exhibitions in 1879, 1880, and 1886.

,_1880.jpg)

Marie Bracquemond, Three Women with Umbrellas (The Three Graces), 1880

Marie Bracquemond, On the Terrace at Sèvres with Fantin-Latour, 1880

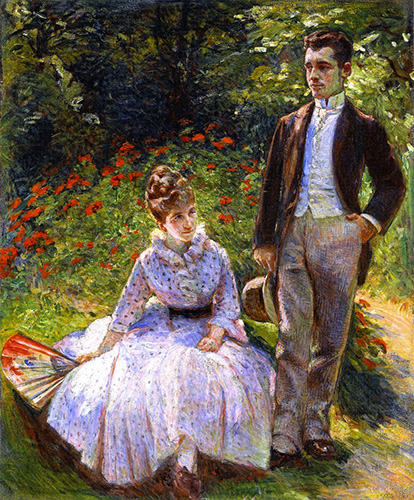

Her husband introduced her to new media and to the artists he admired, as well as older masters such as Chardin. She was especially attracted to the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens. Between 1887-1890, under the influence of the Impressionists, Bracquemond's style began to change. Her canvases grew larger and her colours intensified. She moved out of doors (part of a movement that came to be known as plein air), and to her husband's displease, Monet and Degas became her mentors. Many of her best-known works were painted outdoors, especially in her Garden at Sèvres. One of her last paintings was The Artist's Son and Sister in the Garden at Sèvres.

Marie Bracquemond, The Artist’s Son and Sister in the Garden at Sèvres, 1890

Bracquemond began her career as an academic painter whose polished, realist style had far more in common with the anachronistic work of Salon-approved artists like Cabanel, Regnault, and Gérôme than emerging avant-garde painters like Monet and Degas. However, after having met the latter two, her style began to change dramatically as she absorbed the precepts of Impressionism and by the 1880s her painting could only be described as fully Impressionist. The artist is known for having been something of a recluse, distancing herself from the audience, particularly as she aged. While earlier in her career, she enjoyed going out and painting en plein air like most of her Impressionist colleagues, by mid-career, many of her paintings were made in the garden of her home in the southwestern Parisian suburb of Sèvres.

Marie Bracquemond, Woman in the garden, 1877

Her work after 1886 began to change with her palette becoming increasingly more vibrant. This transformation was due in large part to Bracquemond having met Gauguin in 1886. The two were introduced by Felix, who had befriended the then-impoverished, budding new artist. At Gauguin's encouragement, Bracquemond enhanced her relatively subdued Impressionist palette so that it became much brighter, all of which was ironic given that her husband took exception most of all to her use of color, preferring printmaking in black in white to his wife's chosen medium of oil painting.

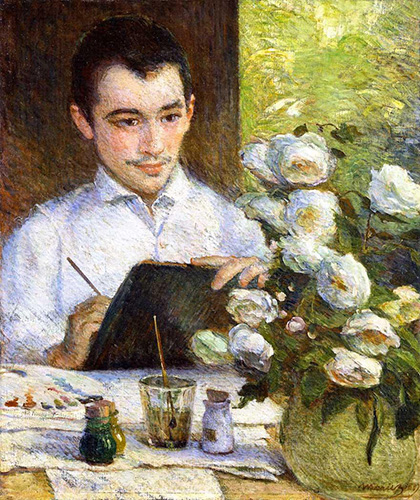

Marie Bracquemond, Pierre Painting a Bouquet, 1887

Although she was overshadowed by her well-known husband, the work of the reclusive Marie Bracquemond is considered to have been closer to the ideals of Impressionism. According to their son Pierre, Félix Bracquemond was often resentful of his wife, brusquely rejecting her critique of his work, and refusing to show her paintings to visitors. In 1890, Marie Bracquemond, worn out by the continual household friction and discouraged by lack of interest in her work, abandoned her painting except for a few private works. She remained a staunch defender of Impressionism throughout her life, even when she was not actively painting. The artist passed away in Paris on January 17, 1916.

Marie Bracquemond, Woman with an Umbrella, 1880