Egon Schiele, the master of explicit nudity in Austrian Expressionism

ArtWizard, 11.11.2019

“Bodies have their own light which they consume to live: they burn, they are not lit from the outside.”

During his short artistic career, Egon Schiele (1890–1918) managed to create an oeuvre that was both symptomatic of and ground breaking for his times. He was placed among the most formative and colorful figures of Viennese Modernism. His own existence was at the

center of his artistic interest, as reflected in countless self-portraits as well as landscapes and cityscapes. Schiele stylized himself in his works and letters as a sage and clairvoyant, as a conduit with an intense sense of reality and truth. Using his unique eccentric gestures and facial expressions, he conveyed the urgency of relentlessly interrogating the body.

Schiele imposed a style based on self-reflection as a quasi-blending of corporeality and sexuality with the existential questions of being. It was through this approach that Schiele was able to find analogies at the level of visual arts at the times when crisis of the individual that was addressed in several ways in philosophy, psychology, literature, and theater in Vienna in the beginning of the 20th century.

A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early 20th century. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality, and the many self-portraits the artist produced, including naked self-portraits. The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele's paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism.

Egon Schiele’s father died when he was 14, and he never got over it. The artist was born in Tulln, Ausrtia and hе talent for drawing was spotted by an eagle-eyed teacher, who encouraged the young boy to pursue a career in arts. When his father died, the experience was of such heaviness, that the artist has never been completely recovered.

“I don’t know whether there is anyone else at all who remembers my noble father with such sadness,’ he would write to his brother-in-law a decade later. “I don’t know who is able to understand why I visit those places where my father used to be and where I can feel the pain… Why do I paint graves and many similar things? Because this continues to live in me.”

In the early 20s, in Vienna the art scene was at the verge of an art revolution, where Gustav Klimt formed the Vienna Secession art movement, proclaiming that what the artist had to do is to free culture from the grips of the establishment. He introduced young Egon Shiele to the works of Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh and other great masters of art.

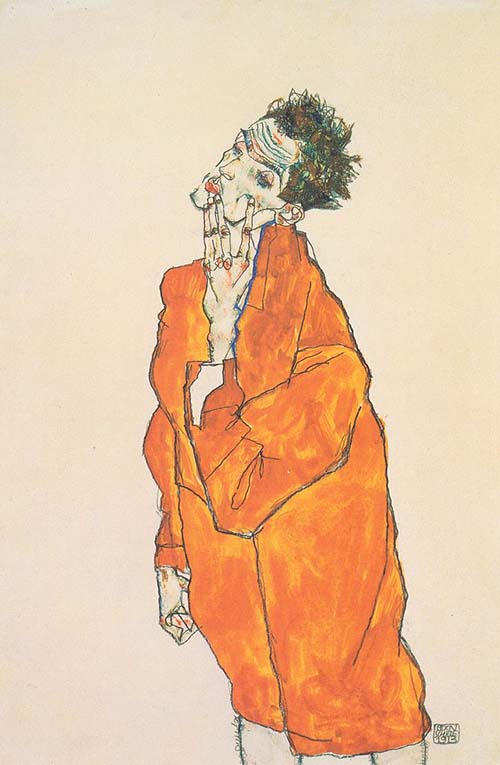

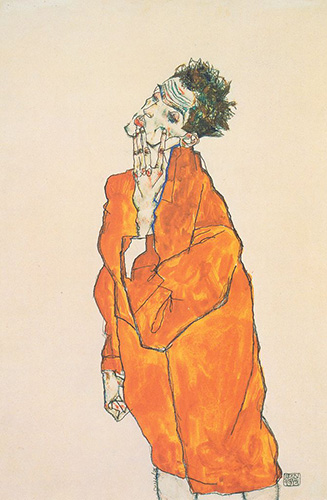

Egon Schiele, Selbstbildnis in oranger Jacke, 1913

Influenced by Klimt, much of Schiele’s art focused on the eroticism and female form. But over time Schiele would distance himself from his mentor’s ornate, shimmering Art Nouveau-inspired aesthetic.

The Expressionist style that Schiele later developed was quite raw and deeply emotional, and executed in sombre and simple colors. Inspired in part by Schiele’s harrowing experience of watching his father’s decline, this shift also reflected his deep interest in human psychology and the powerful influence of Sigmund Freud in turn-of-the-century Vienna.

Event though Klimt and Schiele did not have similar style, they remained close friends, as in 1917, Schiele and Klimt co-founded an exhibition venue called the Vienna Kunsthalle, which they hoped would inspire Austrian artists to stay and work in the country.

From then on, Schiele participated in numerous group exhibitions, including those of the Neukunstgruppe in Prague in 1910 and Budapest in 1912; the Sonderbund, Cologne, in 1912; and several Secessionist shows in Munich, beginning in 1911. In 1911, Schiele met the seventeen-year-old Walburga (Wally) Neuzil, who lived with him in Vienna and served as a model for some of his most striking paintings. Very little is known of her, except that she had previously modelled for Gustav Klimt and might have been one of his mistresses.

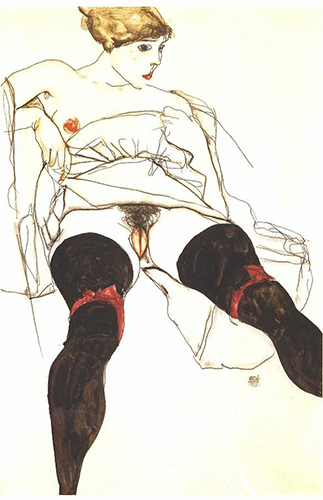

In 1909 Schiele followed Klimt’s example and left the conservative strictures of the Academy. He formed his own movement, the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group), bringing together fellow students who wanted to go in a different direction, including Oskar Kokoschka and Max Oppenheimer. By the early 1910s, Schiele’s work had become an obsessive exploration of the human body. He never shied away from candidly depicting genitalia — female genitalia as well as his own — or from treating subjects that were taboo for the time, such as masturbation or sex between women.

In 1910, Schiele began experimenting with nudes and within a year a definitive style featuring emaciated, sickly-coloured figures, often with strong sexual overtones. Schiele also began painting and drawing children. Egon Schiele’s |Kneeling Nude with Raised Hands", 1910 is considered among the most significant nude art pieces made during the 20th century. Schiele’s radical and developed approach towards the naked human form challenged both scholars and progressives alike. This unconventional piece and style went against strict academia and created a sexual uproar with its contorted lines and heavy display of figurative expression. At the time, the society found the explicitness of his works disturbing.

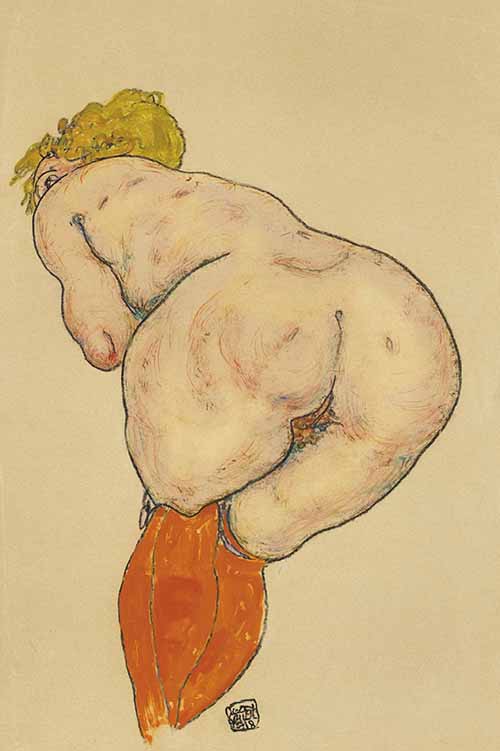

Egon Schiele, Ruckenakt mit orangefarbenen strumpfen, 1918

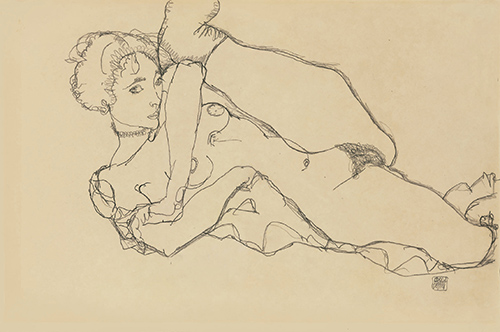

Egon Schiele, Liegender Akt mit angezogenem linken Bein, 1914

Schiele considered drawing his primary art form. The overtly erotic drawings of the artist show very sensual, fleshy, and volumetric nudes that appear in Schiele’s drawings and watercolours from 1914.

"Schiele’s drawings disturb partly because they stop at a point that academic convention regards as raw and unfinished,’ stated Christopher Knight in the Los Angeles Times. ‘Quick, contour rendering was essential to academic training, but for an academic artist it was just the start of a laborious process, which eventually culminated in a finished painting. Schiele intuitively recognised, not unlike French Impressionist painters some 40 years before, that the spontaneity of an early sketch, if handled eloquently, could be the armature for an art of pressing liveliness."

With time, as with changing the theme of his works, concentrating on some obscene for his time depiction of the human body, lead to the situation were his art, and indeed, Schiele himself, were condemned as indecent. Following a need to be in a more solitude place to make his art, in 1911 the artist moved to his home town in Krumau in Czech Bohemia

This move was not really successful, as in the small town, the painting of his nude models disturbed the local society. When villagers spotted a nude model posing outdoors, Schiele was driven out of town, and moved to another village in the area. Again, the artist was prosecuted and was arrested on charges of ‘offences against public morality’ and ‘seduction’ of one of his underage models. Although that charge was ultimately dropped, he spent 24 days in prison, condemned for the indecency of his work. It was a public vilification that belied Schiele’s commercial and critical success, as throughout his career, museums and collectors from across Europe would continue to buy his work.

Egon Schiele, Stadt am blauen Fluss, 1910

,_1913.jpg)

Egon Schiele, Frau in Unterwäsche und Strümpfen (Wally Neuzil), 1913.

Later that year he was reassigned to Vienna, where higher-ups allowed him to pursue his art. He was relatively prolific during the war years, producing cityscapes and landscapes, and even contributing work to exhibitions in Amsterdam, Stockholm and Copenhagen.

The year 1918 promised to be one of great success for Schiele, as in March his work had pride of place at the Vienna Secession’s 49th annual exhibition. But that autumn saw a deadly outbreak of Spanish flu. The pandemic would eventually decimate both Europe and America, resulting in more victims than were claimed by the First World War.

On 28 October 1918, Schiele’s wife Edith, then six months pregnant, contracted flu and died. Just a few days later, on 31 October, Schiele himself passed away. He was 28 years old.

Egon Schiele, Frau mit schwarzen Strümpfen, 1913

Schiele’s artistic legacy is profound, as almost one hundred years after his death, none of the anxiety surrounding Schiele’s erotically charged images has diminished. Few artists have been so starkly frank in their exploration of sexuality or so dangerously close to straining taboo to breaking point.

Despite his short life, Schiele’s work was crucial to the development of Austrian Expressionism.

His aesthetic was a huge influence on contemporaries including Kokoschka; his work also directly influenced artists in generations to come, such as Francis Bacon, Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Tracy Emin, whose work was shown alongside Schiele’s at Vienna’s Leopold Museum in 2015.