Edvard Munch. The Scream!

ArtWizard, 29.07.2019

The Crisis of Modern Consciousness in the work of Edvard Munch

Anxiety can be a spur to creativity, as the works of Edvard show. That of Munch reflects the crisis of modern consciousness with even greater intensity. The personal experiences of a depressive nature corresponded with the pessimistic mood of the era.

Munch was a Norwegian painter, who’s early life was overshadowed by illness, bereavement and the dread of inheriting a mental condition that ran in the family. His painting, The Scream became one of the most iconic images of the art world. In the late 20th century, Minch played a great role in German Expressionism, and the art form that later followed, namely because of the strong mental anguish that was displayed in many of the pieces that he created.

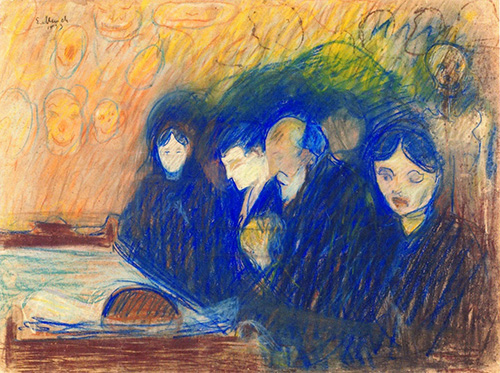

Already as a boy, Munch was confronted by the death that inevitably closes life’s cycle. He was only five when he lost his mother to tuberculosis. A sister died a short time later, and a third became insane. Edvard’s father, a melancholy man, was a doctor who treated the poor of Oslo, so misery was a continual guest in the Munch household. Munch's father suffered of mental illness, and this played a role in the way he and his siblings were raised. Their father raised them with the fears of deep-seated issues, which is part of the reason why the work of Edvard Munch took a deeper tone, and why the artist was known to have so many repressed emotions as he grew up. Munch gives the By the Death Bed and Death in the Sickroom a universal cast by not specifically depicting what he had witnessed. Several versions of The Sick Child are surely his sister.

The sensitive young man feared to succumb to the family fate, when an aunt suggested that painting would be a good way to take his mind off such depressive ideas. She thereby showed him the way to articulate his oppressive anxiety. It cannot be denied that Munch’s artistic uniqueness, the factors in his work that made him pioneer of modern painting, were closely related to his personal circumstances. For confirmation, we only need to compare the works of his early period, up to 1908, with those he painted after the Danish physician, Dr. Daniel Jacobson had cured him in a Copenhagen clinic of the obsessions that led to a near-fatal nervous breakdown. Suddenly his paintings showed no more despairing young girls on The Day After, no panic-stricken men, no sick children, no death and dying, no storm-whipped, darkly ominous landscapes. Munch had recovered his health and his ability to cope with life, but his regained power also entailed a loss of hallucinatory vision and nervous sensibility.

After the transformation in his health life, Munch began to live a bohemian life under the influence of the nihilist Hans Jaeger, who urged him to paint his own emotional and psychological state ("soul painting"). His association with Hans Jaeger, a writer who has shocked the good citizens of Oslo with a novel so sexually explicit that it was promptly banned, brought Munch into contact with Oslo’s Bohemian scene. The artists there had distanced themselves as far from the self-satisfied bourgeoisie as they has in Paris, and they protested against the commercialization of industrial society in a life-style as unconventional as they could manage.

From this would presently emerge his distinctive style. Travel brought new influences and new outlets. In Paris, he learned much from Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Toulouse Lautrec, especially their use of colour. In Berlin, he met Swedish dramatist August Strindberg, whom he painted, as he embarked on his major canon The Frieze of Life, depicting a series of deeply-felt themes such as love, anxiety, jealousy and betrayal, steeped in atmosphere.

From about 1892, to 1908, Munch split most of his time between Paris and Berlin. It was in 1909 that he decided to return to his hometown, and go back to Norway.

During this period, much of the work that was created by Edvard Munch depicted his interest in nature, and it was also noted that the tones and colours that he used in these pieces, did add more colour, and seemed a bit more cheerful, than most of the previous works he had created in years past. It was however when the artist returned back to Norway in his home town Christiania, part of Oslo today, that his legendary work The Scream was conceived.

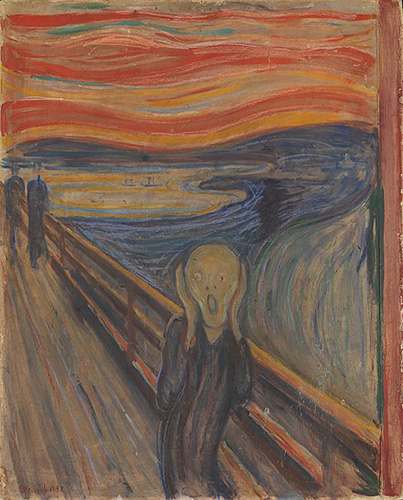

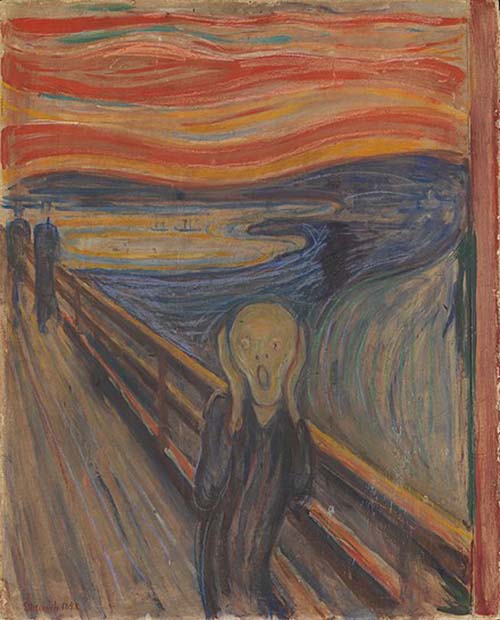

According to Munch, he was out walking at sunset, when he “heard the enormous, infinite scream of nature”. That agonised face is widely identified with the angst of modern man. Essentially, The Scream is autobiographical, an expressionistic construction based on Munch's actual experience of a scream piercing through nature while on a walk, after his two companions, seen in the background, had left him. Fitting the fact that the sound must have been heard at a time when his mind was in an abnormal state, Munch renders it in a style which if pushed to extremes can destroy human integrity. Beginning at this time, and with this painting, Munch included art nouveau elements in many pictures but usually only in a limited or modified way. Here, however, in depicting his own morbid experience, he has let go, and allowed the foreground figure to become distorted by the subjectivised flow of nature. The Scream could be interpreted as expressing the agony of the obliteration of human personality by this unifying force.

Between 1893 and 1910, he made two painted versions and two in pastels, as well as a number of prints. One of the pastels would eventually command the fourth highest nominal price paid for a painting at auction. The 1895 pastel-on-board version of the painting was sold at Sotheby's for a record US$120 million at auction on 2 May 2012. Recently it was actually revealed who was the real owner of the painting, a somewhat millionaire New York banker named Leon Black.

As his fame and wealth grew, the emotional state of the artist remained as insecure as ever. He briefly considered marriage, but could not commit himself. A breakdown in 1908 forced him to give up heavy drinking, and he was cheered by his increasing acceptance by the people of Christiania and exposure in the city’s museums. His later years were spent working in peace and privacy. Although his works were banned in Nazi Germany, most of them survived World War II, ensuring him a secure legacy.

A majority of the works which Edvard Munch created, were referred to as the style known as Symbolism.

Many of Munch's works depict life and death scenes, love and terror, and the feeling of loneliness was often a feeling, which viewers would note that his work patterns focused on. These emotions were depicted by the contrasting lines, the darker colours, blocks of colour, sombre tones, and a concise and exaggerate form, which depicted the darker side of the art which he was designing.