Willem de Kooning. The Artist’s Artist!

ArtWizard, 05.08.2019

“The attitude that nature is chaotic and that the artist puts order into it is a very absurd point of view, I think. All that we can hope for is to put some order into ourselves. When a man ploughs his field at the right time, it means just that”.

An at least equally important representative of Action Painting as Jackson Pollock, but eight-year younger than him was Willem de Kooning. Driven by an acutely perceptive mind, coupled with the determination to achieve – the charismatic de Kooning became one of America’s and the twentieth century’s most influential artists. After an apprenticeship in Holland and Belgium, he decided he wanted to go to America, and arrived there without papers after a fantastic odyssey as a ship’s machinist and seaman. After beginning his figurative style, the artist came under the influence of Miro and his friend, Arshile Gorky and began to depict an inner, pre-existent world, independent of historical reference and external experience. But the more mastery he gained over his means, the more the “landscape of the soul” receded in the background.

The shapes broke up and appeared to shoot beyond the canvas edge. The content of such painting lay in the making visible the painting process, the artists’ actions themselves, although the series of Women, complex, idol-like or demonic female figures, and such painting titles as Suburb in Havana or Merrit Parkway indicate that the references to things seen and experienced were never entirely expunged from De Kooning’s abstractions. This open endedness of artistic stance corresponded to the opening of De Kooning gestures, the unfinished look of his forms.

His paintings are metamorphoses of the visible world and at the same time of his own mental and emotional world. Since these realities changed as incessantly as the artist’s relation to them, his art eludes all stylistic classification. De Kooning style is incredibly vital, and holds a tense equilibrium. Transformation and change are dominant factors in the imagery of this eminently gifted painter.

Indeed, the artist always retained the right of artistic decision and resisted being labelled as an Abstract Expressionist by producing obviously figurative works, unconcerned by the confusion his Women caused among the art experts.

By the late forties and early fifties, Willem de Kooning and his New York contemporaries, including Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Adolph Gottlieb, Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, became notorious for rejecting the accepted stylistic norms such as Surrealism and Cubism by dissolving the relationship between foreground and background and using paint to create emotive, abstract gestures. This movement was variously labelled “Action Painting,” “Abstract Expressionism” or simply the “New York School.” Until this time, Paris had been considered the centre of the avant-garde, and the groundbreaking nature of Picasso’s contributions was frustratingly difficult to surpass for this group of highly competitive New York artists. As De Kooning plainly said once, “Picasso is the man to beat!”.

Along with Jackson Pollock, he finally managed to steal the place under the spotlight from some of the Paris artists and was the reason for the historic shift of attention of the art world from Paris to New York, becoming the Capital of Art after the World War II. If Jackson Pollock was the public face of the New York avant-garde, Willem de Kooning was the “artist’s artist”, who was perceived by many of his peers as its leader. He gained his first critical acclaim in 1948, with his first one-man exhibition held at Charles Egan Gallery at the age of forty-four. This exhibition was essential to the artist’s reputation and showed densely worked oil and enamel paintings, including his now well know black-and-white paintings.

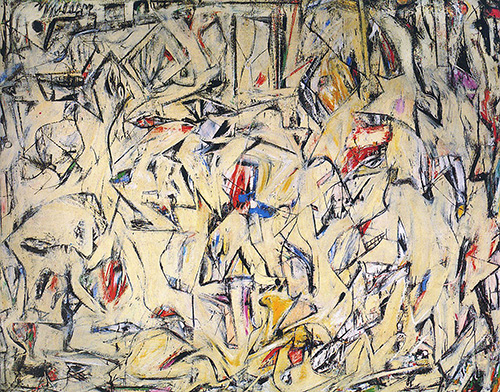

One of the main and most important paintings of the artist is Excavation, completed in 1950, for which he received the Logan Medal and Purchase Prize from the Art Institute of Chicago. Some critics say that this was arguably one of the most important paintings of the twentieth century. It is during this period, when he gained the support from two of the most influential critics at the New York Art Scene – Greenberg and Rosenberg. His success did not prevent him from exploring and experimenting with styles.

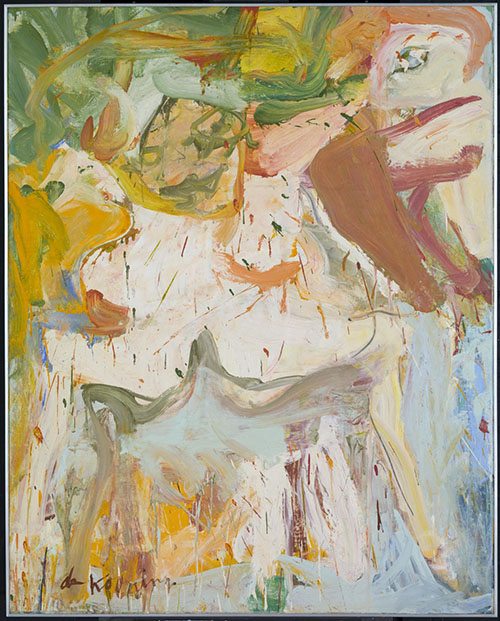

In 1953 he shocked the art world by exhibiting a series of aggressively painted figural works, his famous “Woman” paintings. These women were types or icons much more than portraits of individuals. His return to figuration was perceived by some as a betrayal to the Abstract Expressionist principles, which emphasised abstraction. Although he lost the support of some of the art critics of the time, the New York Museum of Modern Art accepted the artist change in style as an advancement in his work and purchased Woman I in 1953. At the time, what seemed for some as statistically recreationally, to others was clearly avant-garde.

The artist had a prominent career that lasted over seven decades, and over this long time he would work through a wide array of styles. Although he was often associated with Abstract Expressionism, the artist generally rejected any association with a specific art movement. Physical labor and countless revisions were constants in his work, that moved in the wide range from abstraction to figuration, often merging the two. He was known to frequently rework canvases, spending a longtime painting over a canvas, before he scrapes all the work and starting over again.

“I never was interested in how to make a good painting…,” he once said. “I didn’t work on it with the idea of perfection, but to see how far one could go…”