The Woman of Alphonse Mucha...

ArtWizard, 14.10.2019

"The purpose of my work was never to destroy but always to create, to construct bridges, because we must live in the hope that humankind will draw together and that the better we understand each other the easier this will become."

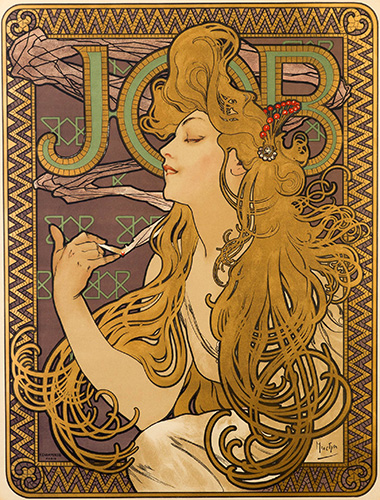

Alphonse Mucha was raised in the shadow of two powerful cultural forces: The Catholic Church and the Slav's desire for independence from the Austrian Empire. Excited by light and color, Mucha's earliest memory was of Christmas tree lights. A baroque fresco in his local church piqued his interest in art, and he moved to Vienna, where he took an apprenticeship as a stage set painter. Surrounded by the explosion of art in the Austrian capital, he was influenced by the works of Hans Makart. Alphonse Mucha is best known for his distinctly stylized and decorative theatrical posters, particularly that of Sarah Bernhardt.

To make a living in the beginning of his career, Mucha made portraits on commissions. This led him to an important mentor, Count Khuen-Belasi, who hired him to paint murals in Emmahof Castle. Mucha's own poverty and popularity was brought into sharper clarity while he worked in the castle. His poverty was such that his one and only pair of trousers grew so shabby that a group of society girls bought him a new pair. Count Khuen-Belasi paid for Mucha's training in fine art in Munich, where he continued to work as an illustrator and developed his unique style. Mucha moved to Paris in 1888 where he enrolled in the Académie Julian and the following year, 1889, Académie Colarossi. The two schools taught a wide variety of different styles. His first professors at the Academie Julien were Jules Lefebvre who specialized in female nudes and allegorical paintings, and Jean-Paul Laurens, whose specialties were historical and religious paintings in a realistic and dramatic style. At the end of 1889, as he approached the age of thirty, his patron, Count Belasi, decided that Mucha had received enough education and ended his subsidies.

In Paris, Mucha found shelter with the help of the large Slavic community. He lived in a boarding house called the Crémerie at 13 rue de la Grand Chaumerie, whose owner, Charlotte Caron, was famous for sheltering struggling artists. When needed, she accepted paintings or drawings in place of rent. Mucha decided to follow the path of another Czech painter he knew from Munich, Ludek Marold, who had made a successful career as an illustrator for magazines. In 1890 and 1891, Mucha began providing illustrations for the weekly magazine "La Vie Popular", which published novels in weekly segments. His illustration for a novel by Guy de Maupassant, called "The Useless Beauty", was on the cover of the 22 May 1890 edition of the book.

The illustrations of Mucha at this period already began to give him a regular income. He was able to buy a harmonium to continue his musical interests and his first camera, which used glass-plate negatives. He took pictures of himself and his friends, and also regularly used it to compose his drawings. The artist became friends with Paul Gauguin, and shared a studio with him for a time when Gauguin returned from Tahiti in the summer of 1893 in late autumn 1894 he also became friends with the playwright August Strindberg, with whom he had a common interest in philosophy and mysticism.

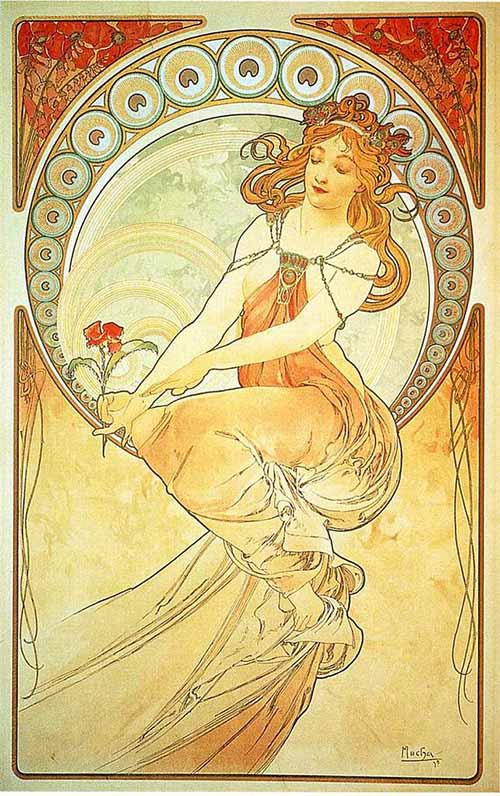

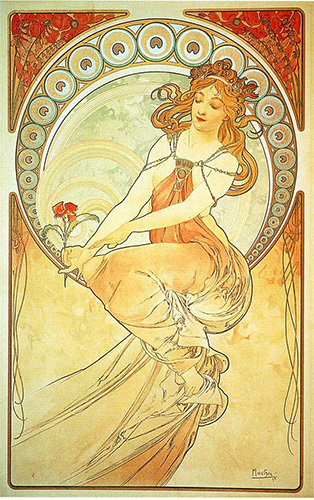

He and Paul Gauguin shared a studio on the Rue Grande Chaumiere and Mucha rigged the studio so that when the door opened beautiful music played. An interviewer in 1900 called the studio, "simply marvelous." It was full of exotic objects and bohemian writers, artists, and musicians who came to work and play. An infamous photograph of Gauguin playing the Harmonium with no trousers on, captures the playful and free-spirited mood of their studio. It was here that Mucha first explored his interest in the occult with August Strindberg, and engaged in hypnotic and psychic experiments with Albert de Rochas and the astronomer Camille Flammarion. All of this experience influenced greatly his style, which became ornate, dynamic, with rich curving lines. In this period, the artist developed his iconic image of a woman, with curves and flowing hair, depicted in pastel robes and with a halo of flowers.

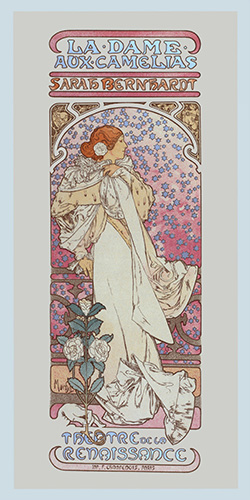

At the end of 1894 the career of Mucha took a dramatic and unexpected turn when he began to work for French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt. As Mucha later described it, on 26 December Bernhardt made a telephone call to Maurice de Brunhoff, the manager of the publishing firm Lemercier which printed her theatrical posters, ordering a new poster for the continuation of the play Gismonda. The play, by Victorien Sardou, had already opened with great success on 31 October 1894 at the Théâtre de la Renaissance on the Boulevard Saint-Martin. Bernardt decided to have a poster made to advertise the prolongation of the theatrical run after the Christmas break and insisting it be ready by 1 January 1897. Because of the holidays, none of the regular Lemercier artists were available.

When Bernhardt called, Mucha happened to be at the publishing house correcting proofs. He already had experience painting Bernhardt as he had made a series of illustrations of her performing in Cleopatra for Costume au Théâtre in 1890. When Gismonda opened in October 1894, Mucha had been commissioned by the French magazine "Le Gaulois", to make a series of illustrations of Bernhardt in the role for a special Christmas supplement, which was published at Christmas 1894, for the high price of fifty centimes a copy.

Brunhoff asked Mucha to quickly design the new poster for Bernhardt. The poster was more than life-size, a little more than two meters high, with Bernhardt in the costume of a Byzantine noblewoman, dressed in an orchid headdress and floral stole, and holding a palm branch in the Easter procession near the end of the play. One of the innovative features of the posters was the ornate rainbow-shaped arch behind the head, almost like a halo, which focused attention on her face.

The poster featured extremely fine draftsmanship and delicate pastel colors, unlike the typical brightly-colored posters of the time. The top of the poster, with the title, was richly composed and ornamented, and balanced the bottom, where the essential information was given in the shortest possible form, just the name of the theater.

Later on, being inspired by friends such as Auguste Rodin, Alphonse Mucha experimented with sculpture and partnered with the goldsmith Fouquet to produce fantastic jewels from gold, ivory, and precious stones. He even created a radiant "Mucha world" in Fouquet's Rue Royale boutique where his statues, stained glass, fountains, mosaics, sculpture, and lighting turned shopping into a theatrical experience. Mucha was in this period of his life pronounced as the greatest decorative artists and even issued books, containing numerous designs of glass, furniture, figures wallpapers.

Besides the other activities, the artist continued with his books, with the illustrated book "Le Pater', issued in 1899, where he explored his spiritual beliefs, namely that art had moral and political purpose. The artist was then famous, but he claimed that he was crushed by the fame, which he described as "robbing me of my time and forcing me to do things that are so alien to those I dream about." His artistic dream was to create an epic painting cycle that would serve as a beautiful illustration of Slav history and that would inspire the Slavic quest for freedom.

To fund his monumental painting epic, Mucha made multiple trips to the USA to find a patron. By executing society portraits in 1909 Mucha finally found his man, the philanthropist Charles Crane, who would finance him for the next twenty years.

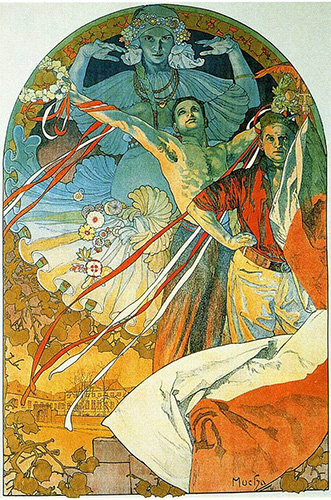

Mucha returned to Prague in 1910 and dedicated himself to his Slav Epic, while simultaneously executing projects such as the Lord Mayor's Hall ceiling which bore the inscription: "Though humiliated and tortured you will live again, my country!" In 1918 Mucha's dream was realized when Czechoslovakia was recognized as an independent nation. Delighted, he set about designing the new nation's postage stamps, banknotes, and coat of arms. In a studio in Zbiroh Castle he toiled at his giant canvases, some of which measured 6x8 meters, and were rigged like ship's sails to haul them up and down. His work required research, and he made regular field trips throughout the Balkans and to consult with historians to ensure that every battle and costume was depicted accurately. His works began to give the Pan-Slavic vision international attention. In 1919 the first phase of his epic work was on tour in the USA, attracting 50,000 visitors per week. The final canvas was completed after seven years and shows the new Czech Republic, protected by Christ, under a rainbow of peace.

Under Nazi occupation the Slav Epic was hidden underground, and under Communism his art continued to be viewed as decadent and bourgeois and did not receive public display. His son Jiri Mucha, devoted much of his life to reviving his father's reputation. The 1960s Art Nouveau revival saw Mucha's style much-copied on British posters for Pink Floyd.

Alfonse Muha, Theatrical Poster Sarah Bernhardt

Alphonse Mucha, Poster 1896

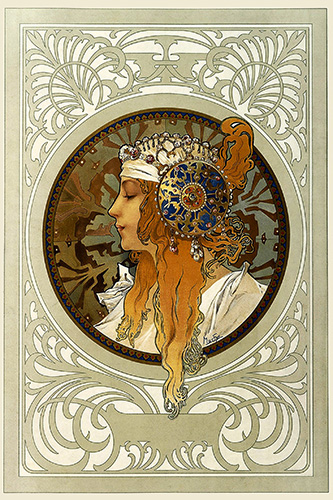

Alphonse Mucha, Byzantine Heads Blond Poster

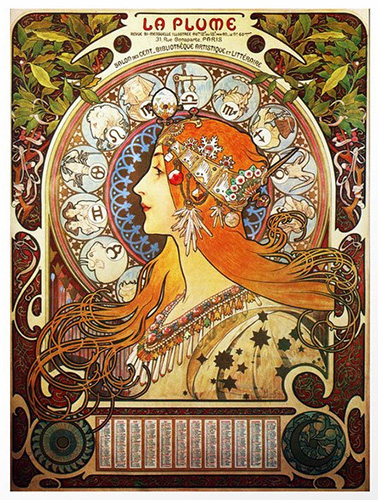

Alphonse Mucha, La Plume Zodiac

Alfonse Miha, Theatrical Poster Art Print featuring Sarah Bernhardt in La Dame aux Camélias

Alphonse Mucha, 8Th Sokol Festival, 1912

Alphonse Mucha Spring, 1896

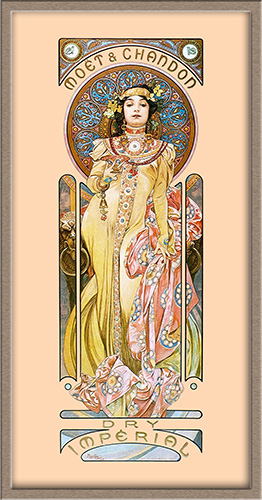

Alfonse Mucha, Moet and Chandon Advertising Poster

Alphonse Mucha, The Times of the Day, 1900