The restless perfectionism of Alberto Giacometti...

ArtWizard, 28.10.2019

"I began to work from memory…but wanting to create from memory what I had seen, to my terror the sculptures became smaller and smaller, yet their dimensions revolted me, and tirelessly I began again, only to end several months later at the same point. Often they became so tiny that with one touch of my knife they disappeared into dust."

Alberto Giacometti, was a Swiss sculptor and painter, best known for his long fragile sculptures of small figures. His work has been compared to that of the existentialists in literature. He was born in Switzerland to an artistic family in 1901. His father was the Post-Impressionist painter Giovanni Giacometti. His father’s second cousin was Symbolist painter Augusto Giacometti and his godfather Fauvist Cuno Amiet. In addition to his three younger siblings, two of Alberto’s cousins were raised in his family home after they became orphaned. His brothers Diego and Bruno also worked as artists.

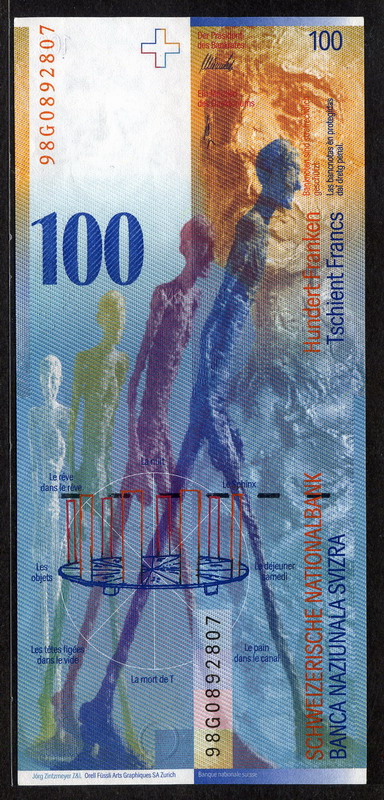

Giacometti was famously extremely self-critical, which motivated his prolific and wide-ranging career: “The more you fail, the more you succeed.” The 100 Swiss francs note features a portrait of Giacometti on one side, and a reproduction of his 1961 sculpture, “L’Homme Qui Marche” on the other.

Alberto Giacometti, L’Homme Qui Marche, 1950-56

Alberto Giacometti and a reproduction of his sculpture in Switzerland 100 Francs

Giacometti grew up among brothers who also showed a penchant for the arts. His brother Diego became known as a furniture designer and served as Giacometti’s model and aide. Another brother, Bruno, became an architect. Alberto Giacometti grew up in the Val Bregaglia alpine valley, a few kilometers from the Swiss-Italian border. His father, Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933) was an impressionist painter esteemed by Swiss collectors and artists. He shared his thoughts with his son on art and the nature of art.

Giacometti left secondary school in Schiers in 1919 and then went to Geneva, where he attended art classes during the winter of 1919–20. After a time in Venice and Padua (May 1920), he went to Florence and Rome (fall 1920–summer 1921), where he encountered rich collections of Egyptian and African . The stylized and fixed, yet striding, figures with their steady gazes and elongated silhouettes proved to have a lasting impact on his art.

In 1927, the artist moved into a studio with his brother, Diego, his lifelong companion and assistant, and exhibited his sculpture for the first time at the Salon des Tuileries, Paris. His first show in Switzerland, shared with his father, was held at the Galerie Aktuaryus, Zurich, in 1927.

The following year, Giacometti met André Masson, and by 1930 he was a participant in the Surrealist circle until 1934. The artist joined André Breton’s Surrealist movement in 1931, as an active member of Breton’s group, Giacometti in no time stood out as one of its rare sculptors. Despite his being expelled in February 1935, surrealist procedures continued to play an important part in his creative work: dreamlike visions, montage and assemblage, objects with metaphorical functions, and magical treatment of the figure.

The issue of the human head was the central subject of Giacometti’s research throughout his life, as well as the reason for his exclusion of the Surrealist group in 1935. In that year, the representation of a head, which seemed to be a common-or-garden subject, was, for him, far from being resolved. The head and, above all, the eyes are the core of the human being and of life, whose mystery fascinated him.

Giacometti experimented with cage-like structures in many of his Surrealist sculptures, evoking the mystery and ambiguity of the world of dreams. He described this period of enigmatic work: “For six whole months, hour after hour passed in the company of a woman who, concentrating all life in herself, made every moment something marvelous for me. We used to construct a fantastic palace in the night (days and night were the same color as if everything had happened just before dawn, throughout this time, I never saw the sun), a very fragile palace of matchsticks: at the slightest false move a whole part of the minuscule construction would collapse: we would always begin it again.”

Giacometti’s work shows the influence of African and Oceanian sculpture. When the young artist developed an interest in African art in 1926, it was no longer a novelty for the modern artists of the previous generation, such as Pablo Picasso and Andre Derain.

Until his death in 1966, Giacometti occupied the small, shabby Paris studio he bought in 1926, despite the commercial, critical, and financial success he experienced during much of his life. His American biographer James Lord referred to the studio as a “dump” and a tree branch famously grew through one of its walls.

From the late 1920s until 1935, Giacometti’s work reflected the ideals of the Surrealists and appeared in exhibitions alongside the work of Joan Miro, Hans Arp and Salvador Dalì. He quickly became a leading Surrealist sculptor.

His first solo show took place in 1932 at the Galerie Pierre Colle, Paris. In 1934, his first American solo exhibition opened at the Julien Levy Gallery, New York. During the early 1940s, he became friends with Simone de Beauvoir, Pablo Picasso, and Jean-Paul Sartre. From 1942, Giacometti lived in Geneva, where he associated with the publisher Albert Skira.

He returned to Paris in 1946. In 1948, he was given a solo show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York. The artist’s friendship with Samuel Beckett began around 1951. In 1955, he was honoured with retrospectives at the Arts Council Gallery, London, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Alberto Giacometti, La clairière, 1950

Alberto Gioacometti, The City Square, 1948

He received the Sculpture Prize at the 1961 Carnegie International in Pittsburgh and the Grand Prize for Sculpture at the 1962 Venice Biennale, where he was given his own exhibition area. In 1965, Giacometti exhibitions were organized by the Tate Gallery, London, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, Denmark, and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. That same year, he was awarded the Grand Prix National des Arts by the French government.

Giacometti met philosopher Jean-Paul Startre in 1941, who is the author of two essential essays about the artist’s work, published in 1948 and 1954, dealing with the issue of perception. Just as significant were his conversations with Sartre’s Japanese translator, Isaku Yanaihara, a professor of philosophy, who posed for Giacometti between 1956 to 1961. In 1948, keen to honour French intellectuals and artists, the French state commissioned Giacometti to design a medal dedicated to Jean-Paul Sartre. The medal was never actually made, but there are drawings for it.

Alberto Giacometti, The Chariot, 1950

Alberto Giacometti, La clairière, 1950

Between 1951 and his death, Giacometti produced a series of “dark heads”, which, together with some anonymous sculpted heads, lent substance to the “generic” man concept, which Sartre would sum up, in 1964, in his novel Les mots, with the sentence: “A whole man, made of all men, worth all of them, and any one of them worth him”. This was Giacometti’s quintessential contribution to the history of the portrait in the 20th century.