How to observe paintings – the importance of signs and symbols in art

ArtWizard 13.07.2020

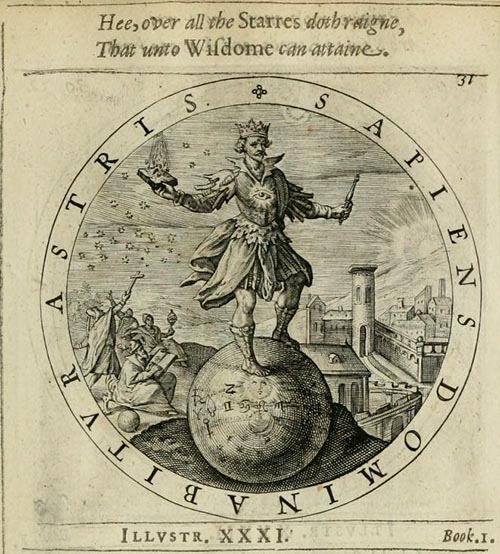

Signs in paintings can be straightforward or ambiguous, include a curtain in a painting, for example, and it may signal a variety of things – intrigue, wealth, a performance – or it may be a simple excuse for an artistic display or brushwork exploring space and colour. Similarly, a heart or a red rose depicted in a painting might suggest love today, but at other periods they may have other meanings. Cesare Ripa published his illustrated Iconologia, a code book to symbols and emblems, in 1603, and it was used widely by artists, one of them being the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer.

Below are some examples of paintings using symbols and signs as part of their narrative stories

Isaac Oliver, The Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, c.1600

The rainbow clutched by Elizabeth I suggests that she has power over the heavens. Thе Latin inscription reads: “No rainbow without sun”. Her sleeve is decorated with a serpent of wisdom, while the disembodied eyes and ears ornamenting her sunburst-colored dress symbolize her aural and visual powers.

Vanitas paintings that exhort moral behavior during our fleeting presence on earth were inspired the Latin text Vanitas Vanitatum ... et omnia vanitas (“Vanity of vanities, all is vanity). Fashions in art change and meanings are lost, but some symbols – a skull to represent death, for example – are still used and need no translation.

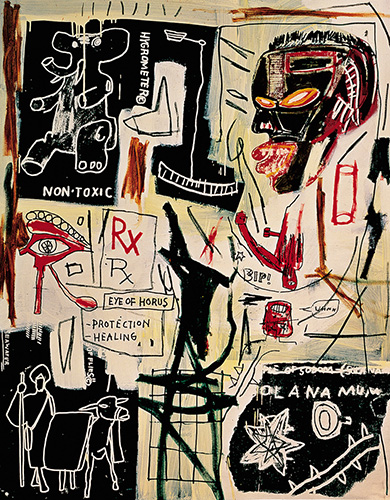

Jean Michel Basquiat, Melting Point of Ice, 1984

Basquiat’s energetic, graffiti - inspired paintings combine clashing and diverse ideas into painted collages with a rippling effect. The African mask-like grinning skull reinvents aspects of the Vanitas paintings, while the artist also includes the protective Egyptian eye of Horus and the symbolically ambiguous seated elephant.

,_1664.jpg)

Claude Lorrain, Landscape with Psyche Outside the Palace of Cupid, (The Enchanted Castle), 1664

In another symbolic painting, the Landscape of Psyche outside the Palace of Cupid (“The Enchanted Castle”), by Claude Lorrain, Psyche’s dilemma is exposed by her languishing pose, Claude conjures a pearly sheen on the dreamy idyllic scene. In the story Psyche’s fate is uncertain: if she peeked at her lover as he slept, she is ruined.

Johannes Vermeer, A Woman Holding a Balance, c.1662

This painting of Vermeer is full of unanswered questions: the scales are balanced, yet the woman is standing by herself holding the table: is her life in balance? A dash of carmine draws attention to her belly: is she pregnant? She is bathed in light, while the painting behind her describes the resurrection and apotheosis of Christ, hinting at salvation through religion.

Adriaen van der Spelt, Flower Still Life with Curtain, 1658

“Tulipomania” was called to describe the craziness of the 1630s, when some tulip bulbs became as valuable as houses. Possessing a painting was a more reliable method of indulging this passion. Presented in this case as a quasi-secret view, the still life is in itself covetable. Artists could depict blooms together that were actually in flower in different seasons.

Evert Collier, Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s “Emblemes”, 1696

A master of trompe-l'œil, Collier specialized in skillful memento mori paintings, reminding the viewers of the inevitability of death. The warning moto Vanitas vanitatum sits with a skull, ah hourglass and a timepiece, while rich tasseled silk, music, wine and fruit suggest having the pleasures of the flesh and earth. The clever juxtapositioning of the musical instruments leads us through the painting.

Not only in visual arts but also in literature, a work of art may not only have subject matter, they may also contain symbols. Certain elements in a work of art may represent, say, a whale, but the whale thus represented may be (as it is in Moby Dick by the 19th-century American writer Herman Melville) a symbol of evil.

In Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is represented a gallery of characters dominated by Anna herself, and a tremendous number of actions in which these characters engage, but there is a constantly recurring item in the representational content—namely, the train. Time and again the train cause or accompanie frustration, disaster, betrayal, and other evils, so much, so that before the novel is ended it becomes apparent that the train here is a symbol of the iron forces of material progress toward which Tolstoy had such great contempt.

Again, if we look carefully on paintings, the observer can often work out what the artist had to say just by looking at the symbols. The Wither’s “Emblemes” for example shows the dark, claustrophobic interior that may focus the observer’s attention to important symbols. Color symbolism or coding is interpreted variously by different cultures. For example, white often stands for purity – Elizabeth I was depicted in white as the “Virgin Queen”, but was also associated sometimes with mourning, green on the other hands can suggest evil, but also hope. Red can convey danger or sexuality and in some far east countries – happiness.

Colors, light and different objects in an artwork can have a lot to tell the observer about the inner world of the artist. In the next article, we will present how important is the figure of the artist in the works of art, as many artists depicted themselves on portraits and paintings, with or without using symbols.