The Zipper colors of Barnett Newman

ArtWizard, 02.12.2019

"A painter is a choreographer of space"

Painter and theorist Barnett Newman was one of the most intellectual artists of the New York School. He is seen as one of the major figures in abstract expressionism and one of the foremost of the painters using monochrome colors. His paintings are existential in tone and content, explicitly composed with the intention of communicating a sense of locality, presence, and contingency.

Newman is generally classified as an Abstract Expressionist on account of his working in New York City in the 1950s, associating with other artists of the group and developing an abstract style which owed little or nothing to European art. However, his rejection of the expressive brushwork employed by other abstract expressionists such as Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko, and his use of hard-edged areas of flat color, can be seen as very close to the minimalist works of artists such as Frank Stella.

Newman believed that the modern world had rendered traditional art subjects and styles invalid, especially in the post-World War II years shadowed by conflict, fear, and tragedy. Newman wrote: "old standards of beauty were irrelevant: the sublime was all that was appropriate - an experience of enormity which might lift modern humanity out of its torpor."

The artist was born and raised in New York and his family was Polish Jewish immigrants. Newman became interested in painting in high school. In parallel with art education received a philosophical degree. After graduation, he worked in various fields, and in 1940 completely gave up painting for four years, devoting himself to the study of ornithology. Later Newman destroyed all of his early work. Mature paintings with vertical and horizontal lines at first were perceived by audiences and critics negatively and Newman received recognition only in the last years of his life.

His approach to art making was shaped by his studies in philosophy at The City College of New York and his political activism. In 1933, he ran for mayor of his city on a write-in ticket with a cultural platform, and he maintained a keen awareness of political issues such as Nazism and the atomic bomb. For him, art was an act of self-creation and a declaration of political, intellectual, and individual freedom. Master of witticisms, he once quipped: “aesthetics is to artists as ornithology is to the birds.” Newman’s artistic career was late-blooming and began in fits and starts. He was around 30 when he started painting, having spent the previous decade teaching, writing, studying, and working in his father’s menswear store. He deemed much of his early work unworthy of consideration and destroyed it. It was not until 1944 that he considered his work mature.

Newman's pictures were a decisive break with the gestural abstraction of his peers. Instead, he devised an approach that avoided painting's conventional oppositions of figure and ground. He created a symbol, the "zip," which might reach out and invoke the viewer standing before it - the viewer fired with the spark of life.

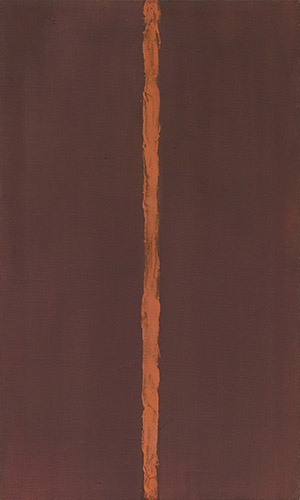

In 1948, with the completion of a painting titled “Onement I”, Newman found his voice. It was in this work that he hit upon what would become the signature motif that defined all of his paintings to come: a vertical band connecting the upper and lower margins of the painting that he called a “zip.” His zips streak through fields of color in spare compositions that prompted critics to describe him as a “color field” painter and minimalist. Newman, however maintained his own opinion of his abstract works. Claiming that he sought “to start from scratch, to paint as if painting never existed before,” he saw his compositions as forms of thought, as expressions of the universal experience of being alive and individual.

Barnett Newman, Onement I, 1948

Barnett Newman, The Wild, 1950

Although Newman's paintings appear to be purely abstract, and many of them were originally untitled, the names he later gave them hinted at specific subjects being addressed, often with a Jewish theme. Two paintings from the early 1950s, for example, are called “Adam and Eve”. Other examples are “Uriel”, 1954, and “Abraham”, 1949 a very dark painting which, as well as being the name of a biblical patriarch, was also the name of Newman's father, who had died in 1947.

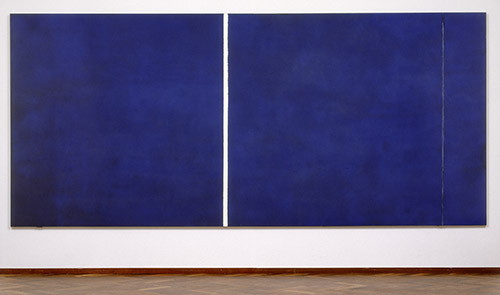

In Newman's best paintings, such as “Cathedra” 1950-1951 and “Vir heroicus sublimis” 1950-1951, the imagery consists of a single field of color that is inflected by one or two thin vertical bands. But the paint is applied with light, feathery brushstrokes that blend softly into one another and nowhere permit the barest sensation of tactile pigmentation. His rich pictorial space is created through varying densities of a particular color rather than through lines or discrete shapes. In this sense, his paintings are purely optical and eschew the perceptual values of objects or spaces in the world outside of painting.

Barnett Newman, Cathedra, 1957 (gallery view)

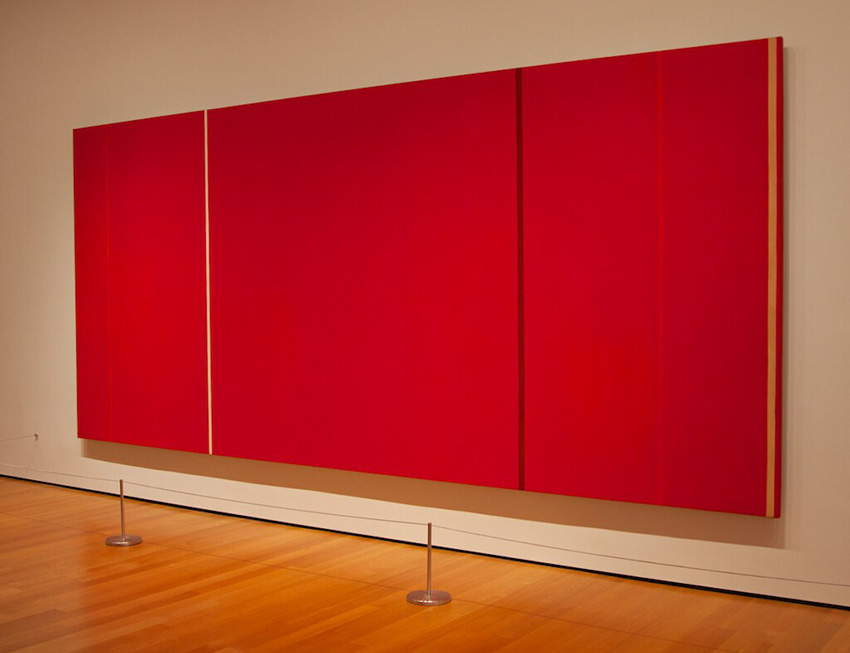

Barnett Newman, Vir heroicus sublimis, 1950-51, (gallery view)

The “Stations of the Cross” series of black and white paintings 1958–1966, begun shortly after Newman had recovered from a heart attack is considered as the peak of his achievement. The series is subtitled “Lema sabachthani” - "Why have you forsaken me" - the last words spoken by Jesus on the cross, according to the New Testament. Newman saw these words as having universal significance in his own time.

Newman's late works, such as the series named “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue”, use vibrant, pure colors, often on very large canvases. For example, “Anna's Light “, 1968 that was named in memory of his mother who had died in 1965, is his largest work, 8.5 meters wide by 2.7 meters high.

Later on, Newman experimented with some shaped canvases, that lead to his work named “Chartres”1969, that is triangular. These later painting is executed in acrylic paints and not in the oil paint as his earlier works. Though he concentrated primarily on painting, Newman also made sculpture. In that period, Newman also returned to sculpture, making a small number of sleek pieces in steel. The “Broken Obelisk”, 1963, is the most monumental and best-known work of Newman, depicting an inverted obelisk whose point balances on the apex of a pyramid. Besides the sculptures, Newman also made a very interesting series of Lithographs, the “18 Cantos”, 1963–64 which, according to Newman, are meant to be evocative of music.

,_1963-64.jpg)

Barnett Newman, Canto V (from 18 Cantos), 1963-64

,_1963.jpg)

Barnett Newman, Canto VII (from 18 Cantos), 1963-64

,_1963-64.jpg)

Barnett Newman, Canto XIV (from 18 Cantos), 1963-64

Besides his very avant-garde way or work, it was only around the1960s, at the last decade of his life, when the artist achieved public acclaim for his work. His anarchic independence and uncompromising stance may have contributed to his slow acceptance, but these deep-seated forces within him also shaped his art. Reflecting on his work towards the end of his life, he declared, “One of its implications is its assertion of freedom…if (it were read) properly it would mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism.