HANS HOFMANN's fundamental laws of painting

ArtWizard 17.02.2020

"Color is a plastic means of creating intervals... color harmonics produced by special relationships, or tensions. We differentiate now between formal tensions and color tensions, just as we differentiate in music between counterpoint and harmony."

Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) is one of the most important figures of American art in the 20th century. Celebrated for his exuberant, color-filled canvases, and renowned as an influential teacher for generations of artists, Hofmann became famous first in his native Germany, then in New York and Provincetown. Hofmann was the only painter of the New York School, that was directly involved in the European modernism of the early-20th century and played pivotal role in the development of Abstract Expressionism. Clement Greenberg, who was strongly influenced by Hofmann's ideas, claimed he was "in all probability the most important art teacher of our time."

Between 1900 and 1930, Hofmann’s early studies, decades of painting, and the schools of art he created, took him to Munich, to Paris, then back to Munich. By 1933, and for the next four decades, he lived in New York and in Provincetown. Hofmann’s evolution from foremost modern art teacher to pivotal modern artist brought him into contact with many of the foremost artists, critics, and dealers of the twentieth century: Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Wassily Kandinsky, Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Betty Parsons, Peggy Guggenheim, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and many others. His successful career was supported by the postwar modern art dealer Sam Kootz, as well as by the art historian and critic Clement Greenberg.

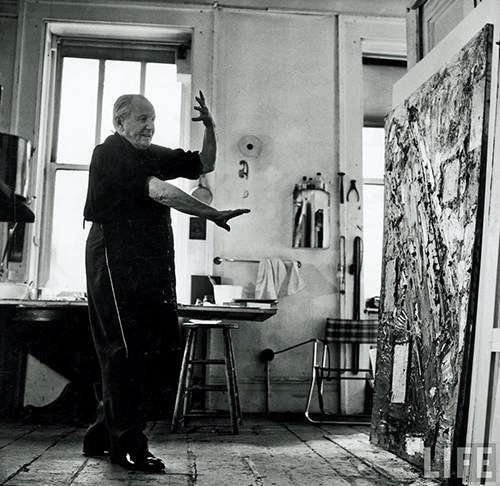

Hofmann was 64 years old and a lot of time has passed from his first to his second solo exhibition at “Art of This Century”, the gallery of Peggy Guggemheim and took place in New York in 1944. At this time, Hofmann balanced the demands of teaching and painting until he closed his school in 1956. Doing so enabled him to renew focus on his own painting following the style of Abstract Expressionism, and for the next twenty years, Hofmann’s voluminous output, powerfully influenced by Matisse’s use of color and Cubism’s displacement of form, developed into an artistic approach and theory he called “push and pull,” which he described as interdependent relationships between form, color, and space.

Hans Hofmann, Still Life Interior, 1941

From his early landscapes of the 1930s, to his paintings of the late 1950s, and his abstract works at the end of his career upon his death in 1966, Hofmann continued to create boldly experimental color combinations and formal contrasts that transcended genre and style.

Hans Hofmann, Magenta and Blue, 1950

Hans Hofmann, Laburnum, 1954

Born Johan Georg Albert in Weissenberg, Bavaria in 1880, Hofmann was a precocious child, showing early inclinations towards mathematics, music, science, literature, and art. When he was six years old, his family moved to Munich where his father had secured a job in the government bureaucracy.

Hofmann's family hoped that he would develop his talents in science, but by the time he had turned eighteen he had decided to pursue art and enrolled in Moritz Heymann's art school in Munich, where he was fascinated with Impressionists. Soon after, he met a patron who enabled him to support himself as an artist in Paris. Around this time the artist met Maria ("Miz") Wolfegg (his 1902 portrait of her represents an early example of the influence of Impressionism on his work). The couple would not marry until 1924, but she accompanied him to Paris in 1904 and they would remain there until 1914. Hofmann was on a visit to Germany when war broke out that year, and he was unable to return to Paris to salvage his pictures, which were all lost.

On return to Munich, Hofmann established his own art school. Its fame soon spread internationally and his first visit to the United States, in 1930, was occasioned by an invitation from a former student, Worth Ryder, to teach a summer session at UC Berkeley. He visited again, and then on his third visit, with political tensions rising in Europe, Hofmann decided to stay and began teaching in New York at the Art Students League. He opened the “Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts” in 1933, and two years later opened a summer school in Provincetown, MA.

,_1935.jpeg)

Hans Hofmann, Untitled (Interior Composition), 1935

Hofmann would continue to work as a teacher until 1958, yet his circumstances in the mid-1930s enabled him to find more time for his own painting. He had not had a solo exhibition since his first one in Berlin in 1910. Many years later, in 1944 he had a second one, at the “Art of This Century Gallery” of Peggy Guggenheim in New York.

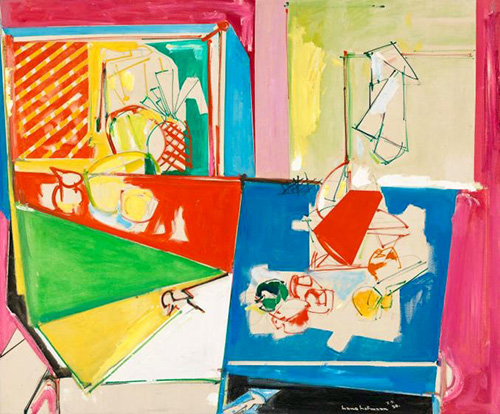

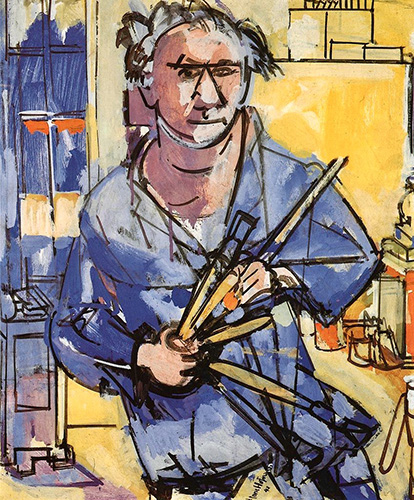

Most of the artworks Hofmann exhibited in that show was quite conservative in comparison to the style of some of other artists in Guggenheim's circle. The painting ”Self-Portrait with Brushes”(1942) is typical of his style at this time. Inspired by his surroundings of his home in Provincetown, it was also stylistically eclectic.

Hans Hofmann, Self-Portrait with Brushes, 1942

Surrealist-influenced artists around Guggenheim's gallery also encouraged Hofmann’s style to move in that direction and his work gradually became more abstract and infused with mythic and primitive imagery, resulting in pictures such as “The Wind” (c.1944). Some critics even speculated that Hofmann's experiments with drip painting were the inspiration for Pollock's famous use of the method. In the early 1950s, Hofmann's pictures became richer in feel, and using thick impasto with surfaces built up in layers and rectangular forms floating on areas of saturated color.

Hans Hofmann, The Wind, c.1944

Hofmann's work as a teacher, his emigration from Europe, and his singular style all contributed to his late recognition as a major painter. Nevertheless, he received many awards and honors in his later life. A retrospective of his work was organized by Clement at Bennington College in 1955. Along with Philip Guston and Franz Kline, Hofmann represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1960. And in 1963, the Museum of Modern hosted a retrospective of his work that toured the world. His success at the time was clouded by the death of his wife Miz in 1963, but two years later Hofmann married again, and he would go on to dedicate a series of paintings to his young German wife, Renate Schmitz, that now hang in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hofmann past away in New York in 1966 at 86 years.

Hans Hofmann, Miz-Pax Vobiscum, 1964

Hofmann was not only a prominent artist, but a man with great ideas, most of them built up from his extensive reading in German philosophy, and this established his lifelong habit of thinking in dualities - in thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. He was a particular adherent of the ideas made popular by Adolph von Hildebrand in his book “The problem of Forms in the Visual Arts”. Based on such theories, Hofmann avoided any suggestion that a modernist artist or critic must distinguish between abstraction and representation, or between gestural, expressionistic styles and geometric forms.

One of his most interesting notions was that he considered the form of a work of art always having in mind the space on which - and in which - it resided. "Form must be balanced by means of space," Hofmann wrote in 1932, "...form exists because of space and space exists because of form." In any work of art, he looked for a visual unity and form that stimulated interest in the viewer, whether pleasing to the eye or not.

Hofmann became famous with his theory of "Push and Pull". He believed that modern artists should evoke pictorial space not in the traditional manner by modeling form with the use of atmospheric perspective, but by using contrasts of color, shape, and surface. Only in this way could an artist stay true to the two-dimensional way the canvas shows a work to the spectator. These tensions between form and color were crucial to a painting's success, Hofmann believed, and referred to them as the "push and pull" within a picture.

Although Hofmann's idea was grounded in aesthetics, the notion of "push-and-pull" may have been influenced by the American modernist painter John Martin. In 1913 he wrote, "[New York is] made of powers [that] are at work pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards... I see great forces at work...the large buildings and the small buildings; the warring of the great and the small...feelings are aroused which give me the desire to express the reaction of these 'pull forces.'"

Another one of the great Hofmann’s ideas was his theories about the fundamental laws of a painting. In 1932 he writes …."Painting as a whole, possesses fundamentals. The highest law of painting is: The entity of the picture plane must be preserved. This entity is its essential two-dimensionality...this law connotes at once: the picture plane must achieve a three-dimensional effect (as distinguished from illusion) by means of the creative process." Hofmann cared little for any form of visual trickery or optical illusion in painting - he believed such devices defied the purity of the creative act on canvas. He believed that since a canvas was, by its nature, a flat surface, it should be treated as such. To apply anything to it other than paint was, in a sense, cheating the art form.

Hans Hofmann, Song of the Nightingale, 1964

Hofmann formed several more rules about painting, all of which were grounded in the Marxist belief that an artist is shaped and conditioned by the historical circumstances that surround him, and can only achieve as much as those circumstances will allow. However, above all else, Hofmann believed that an artwork's meaning should be important to the creator. He also believed that historical and/or political content was an affront to the purity of art itself. And, regarding the necessity of speaking to one's historical moment, Hofmann once added his own caveat, late in life, while addressing some artists: "You belong to a certain time. You are yourself the result of time. You are the creator of this time."