Erotic flowers with Georgia O'Keeffe

ArtWizard 02.03.2020

“Colors & line & shape seem for me a more definite statement than words.”

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986) was a major figure in American art who, remarkably, maintained her independence from shifting artistic trends, staying in the movement of the American Modernism. She painted prolifically, and almost exclusively, the flowers, animal bones, and landscapes around her studios in Lake George, New York, and New Mexico, and these subjects became her signature images. She remained true to her own unique artistic vision and created a highly individual style of painting, which synthesized the formal language of modern European abstraction and the subjects of traditional American pictorialism.

Georgia O'Keeffe, The White Flower, 1932

O'Keeffe studied and ranked at the top of her class at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. Due to typhoid fever, she had to take a year off from her education. In 1907, she joined the Art Students League in New York, where she studied in the classes of William Meritt Chase and Kenyon Cox.

In 1908 O’Keeffe won the League's William Merritt Chase still-life prize for her oil painting Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot. Her prize was a scholarship to attend the League's outdoor summer school in New York. While in the city, O'Keeffe visited galleries, co-owned by her future husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The gallery 291 promoted the work of avant-garde artists from the United States and Europe as well as prominent photographers.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot, 1908

In 1908, O'Keeffe found out that she would not be able to finance her studies. Her father had gone bankrupt and her mother was seriously ill with tuberculosis. The artist was not interested in creating a career as a painter based upon the mimetic tradition which had formed the basis of her art training, so she took a job in Chicago as a commercial artist and worked there until 1910, when she returned to Virginia to recuperate from measles and later moved with her family to Charlottesville. She did not paint for four years, and said that the smell of turpentine made her ill. She began teaching art in 1911. One of her positions was her former school, Chatham Episcopal Institute in Virginia.

She took a summer art class in 1912 at the University of Virginia from Alon Bement, who was a Columbia University Teachers College faculty member. Under Bement, she learned of innovative ideas of Arthur Welsley Dow, a colleague of her instructor. Dow's approach was influenced by principles of Japanese art regarding design and composition. She began to experiment with abstract compositions and develop a personal style that veered away from realism. From 1912 to 1914, she taught art in the public schools in Amarillo in the Texas Panhandle, and was a teaching assistant to Bement during the summers. She took classes at the University of Virginia for two more summers. She also took a class in the spring of 1914 at Teachers College of Columbia University with Dow, who further influenced her thinking about the process of making art. Her studies at the University of Virginia, based upon Dow's principles, were pivotal in O'Keeffe's development as an artist. Through her exploration and growth as an artist, she helped to establish the movement named American Modernism.

The vision of Georgia O’Keeffe, which evolves during the first twenty years of her career, continued to inform her later work and was based on finding the essential, abstract forms in the subjects she painted. With exceptionally keen powers of observation and great finesse with a paintbrush, she recorded subtle nuances of color, shape, and light. Subjects such as landscapes, flowers, and bones were explored in series, or more accurately, in a series of series. Generally, she tested the pictorial possibilities of each subject in a sequence of three or four pictures produced in succession during a single year. But sometimes a series extended over several years, or even decades, and resulted in as many as a dozen variations.

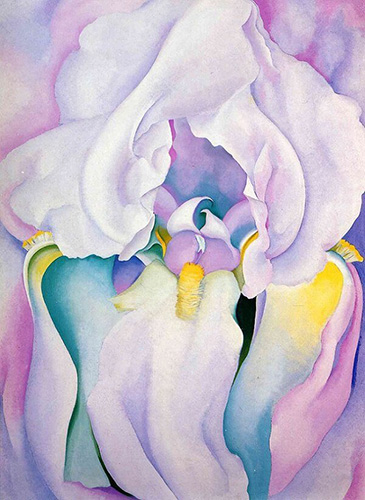

Georgia O'Keeffe, Light Iris, 1924

By the mid-1920s, after an initial period of experimentation with various media, techniques, and imagery, O'Keeffe had already developed the personal style of painting that would characterize her mature work. During the 1930s she added an established repertory of color, forms, and themes that reflected the influence of her visits to New Mexico. For the most part, her work of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s relied on those images already present in her art by the mid-1940s.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Red Canna, 1924

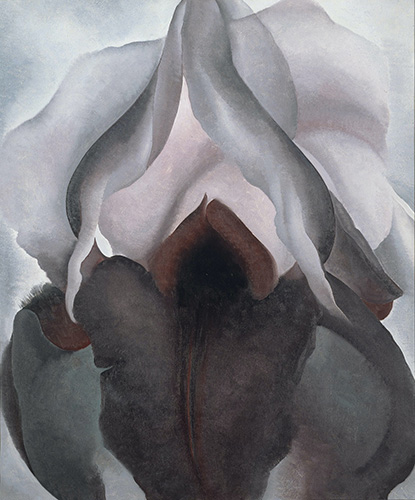

Georgia O'Keeffe, Black Iris, 1926

O'Keeffe's flower paintings have often been called erotic, which is not exactly wrong, but the emphasis is misplaced. It would be surprising if an artist with her passion for the transcendent did not make use erotically charged imagery. Reducing her flowers to symbols of female sexuality is however, a trivializing mistake, for the sexual particulars matter less in art with the aspiration that the vivid and more universal sensation of a joyful release into another world beyond the usual distinctions.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music - Pink and Blue No.2, 1918

Georgia O'Keeffe, Abstraction - White Rose, 1927

O'Keeffe's interest in the scale of transcendence let her to violate certain boundaries. Not only did she make the large small and the small large, but she took serious chances with color, sometimes upsetting conventions of visual harmony in order to startle the eye into new kinds of seeing. She liked to stress visual edges that have metaphysical implications: between night and day, earth and sky, life and death. She was not afraid of the large, symbolic reverberation; her bones often seem strangely alive, the flowers of the desert. Through her repeated reworkings of familiar themes she produced an enormous body of work that in intensely focused and unusually coherent.

The subjects O'Keeffe painted were taken from life and related either generally or specifically to the places where she had been. Through her art she explored the minute details of a setting's or an object's physical appearance and thereby came to know it even better. Often her pictures convey a highly subjective impression of an image, although it is depicted in a straightforward and realistic manner. Such subjective interpretations were frequently colored by important events in the artist's personal and professional life. Their impact on her work was often unconscious, as the artist acknowledged late in life.

Georgia O'Keeffe continued to paint into the 1970s, her almost complete loss of eyesight and ill health during the last fifteen years of her life significantly curtailed her artistic productivity. Her eye problems began in 1968, and by 1971 macular degeneration caused her to lose all her central vision, leaving her, eventually, with only some peripheral sight.

The personal life of Georgia O’Keeffe was as interesting and troubled as her artistic searches.

In June 1918, O'Keeffe accepted Stieglitz's invitation to move to New York and accept his financial support. Stieglitz, who was married to a woman named Emmeline Obermeyer, moved in with her.

In February 1921, Stieglitz's photographs of O'Keeffe were included in a retrospective exhibition at the Anderson Galleries. Stieglitz started photographing O'Keeffe when she visited him in New York City to see her 1917 exhibition, and continued taking photographs, many of which were in the nude. It created a public sensation. When he retired from photography in 1937, he had made more than 350 portraits and more than 200 nude photos of her. In 1978, O’Keeffe wrote about how distant from them she had become, "When I look over the photographs Stieglitz took of me—some of them more than sixty years ago—I wonder who that person is. It is as if in my one life I have lived many lives."

In 1924, Stieglitz was divorced from his wife Emmeline, and he married O'Keeffe. For the rest of their lives together, their relationship was, "a collusion... a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word. Preferring avoidance to confrontation on most issues, O'Keeffe was the principal agent of collusion in their union," according to biographer Benita Eisler. They primarily lived in New York City, but spent their summers at his family home, Oaklawn, in Lake George in upstate New York.

On March 6, 1986 O'Keeffe died in St. Vincent's Hospital in Santa Fe, having almost reached her goal of living to 100. She was 98 years old.

About this moment she had once said: "When I think of death, I only regret that I will not be able to see this beautiful country anymore... unless the Indians are right and my spirit will walk here after I'm gone.” At her request, there was no funeral or memorial service, though her ashes were scattered from the top of the Pedernal over the landscape she had loved for more than half a century.