Chen Danqing is the author of the most expensive work of Chinese contemporary art (continuation)

ArtWizard 28.05.2024

Continuation of Chen Danqing is the author of the most expensive work of Chinese contemporary art

Cover photo of the article © Courtesy of The International Arts And Culture Group

In 1982, Chen Danqing left his job at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and moved to New York, USA, where postmodern art was flourishing, to devote himself fully to painting, become a professional artist and continue his studies at the Art Students League of New York.

In the early 1980s, the artist painted in the style of socialist realism, and was once named by the government as one of the most talented painters in China. Beginning with a series of paintings of Tibetans in the mid-1980s, the artist began to lose official support for his work. He was represented exclusively by the Wally Findlay Galleries in New York, Palm Beach, Beverly Hills and Paris. Chen broke with the patterns of bureaucracy, and his Tibet Series, painted under the influence of French realist Jean-François Millet, in turn had a huge influence on the emerging Native Soil Painting movement. Chen said that French paintings illustrating rural scenes strongly influenced him to "paint smaller and simpler like Millet and Courbet" and "paint what we see".

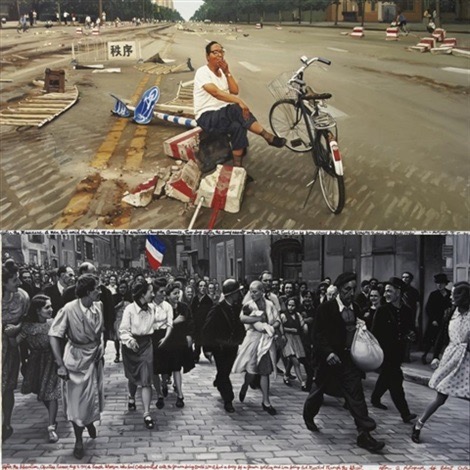

Chen then tried to give a new reading to historical paintings. In the early 1990s, he created a series of paintings on two or three or more columns, placing a number of famous historical works next to contemporary images, with the aim of revealing similarities and differences in human behaviour and concepts throughout historical development. In 1995 he created a work entitled Still Life, 2 metres wide and 15 metres long, on ten columns, comprising nine drawings of contemporary installation art. In September 2006, Street Theater, which he created in 1991, was sold at auction in New York for USD 1.47 million. In this two-column work, he combined an image of a street in Beijing taken by the American photographer David Turnley with an image of another street in France taken by the famous war correspondent Robert Capa. He organised exhibitions of the paintings in Taipei, Taiwan in 1995 and Hong Kong in 1998.

Chen Danqing, Street Theater (in 2 parts), 1991

Courtesy Tang Contemporary Art

In 2000, at the invitation of Tsinghua University, Danqing returned to China to work as a professor at the Institute of Fine Arts and took his students to the Beijing road village to paint farmers, veterans, underground mine workers. He always insisted on painting in a realistic style. In October 2004, he resigned due to declining enrolment in his department, and in 2007, he officially retired from the institute and devoted himself solely to writing and painting.

In 2001, on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Tsinghua University, Chen Danqing painted Traditional Chinese Studies Institute. It is the only large-format canvas (187 x 223 cm) that the artist created during his five years of study at this university. It represented five great academic masters of modern Chinese history, namely (from left to right) Zhao Yuanren, Liang Qichao, Wang Guowei, Chen Yinke and Wu Mi. This national institute of sinology was founded by Tsinghua University in 1925 and then closed in 1929. As its name suggests, it specialised in teaching Chinese culture. The five masters mentioned above worked on this. This was the first time Chen took real personalities as his subject, revealing the distinctive characteristics of each of them surprisingly well. In the overall brown and yellow tone - this work evokes a strong atmosphere of nostalgia, and a stable and deep strength is noticed in the faces.

Chen Danqing, Traditional Chinese Studies Institute, 2001

Courtesy Tang Contemporary Art

"In my early years in Tsinghua, my life and work changed a lot. I faced many difficulties in the student recruitment process because any negotiation with the institution was in vain. The number of interviews I gave to the media multiplied and my writing work increased, added to the fact that I went back to my mother in the United States twice a year, I hardly had time to paint. I even had to take advantage of Spring Festival to make my only creation at Tsinghua, a Traditional Chinese Studies Institute." - Chen wrote, recalling his days there.

Chen Danqing, Smartphones, 2016

Courtesy Tang Contemporary Art

In the extremely interesting and contemporary cycle Disguise and Painting from Life, painted between 2014 and 2017, there is a marked contrast with Tibetan paintings. Here, Chen Danqing depicts young, beautiful Chinese models dressed in expensive colourful dresses and make-up, or in the ripped jeans and hoodies that are an export of American pop culture and are now ubiquitous around the world. Creating the series has more in common with an expensive advertising campaign or fashion shoot than with studio painting. For his paintings, the master uses live models supplied by China Bentley Culture and Media Company, who are posed and dressed by a renowned stylist as if for a fashion photo shoot. He paints over many hours what is captured in moments in the photograph. Unlike posing in a fashion editorial showing off gloss and the appearance of perfection, the models are captured in the in-between moments behind the scenes in moments of relaxation, boredom, and texting on the phone. Chen captures these moments just as he did in his Tibetan series, but they are moments of idleness in a contemporary culture obsessed with luxury. The subjects are not absorbed in daily labour, and their smooth, painted, wrinkle-free faces do not reflect the hardships of agrarian life. These figures are part of global capitalism, carefree, obsessed with luxury and beauty. They are distracted by their phones, bored, disconnected, self-absorbed, as in the painting Smartphones, 2016, where two young women sit almost back-to-back and stare into their phones, barely paying attention to each other or the dog sitting between them.

Chen Danqing, Veil, 2017

Courtesy Tang Contemporary Art

An interesting juxtaposition and tension between the so-called East and West persists in the artist's use of Chinese models with Western-style figures. Some paintings, such as Veil, 2017, depicting a standing woman in a wedding outfit, or Cigarette, 2017, in which a young woman, sumptuously dressed in a long white dress and a large black hat, holds a cigarette, are reminiscent of the portraits of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century artist John Singer Sargent or the photographs of Irving Penn. In Artificial Flowers, 2017 - this juxtaposition of Eastern and Western influences is most evident in the traditional Japanese outfits of seated women and Western outfits of standing men. The female figures look passively away from the viewer - quite like in traditional Western figurative painting, in which the woman is objectified, meant for the enjoyment of the male viewer - while the male figure stands above them and looks directly at the viewer.

Chen Danqing, Artificial Flowers, 2017

Courtesy Tang Contemporary Art

The subjects of this series by Chen Danqing are as far removed as possible from the harsh realities of the rural life of his Tibetan subjects, which Chen himself experienced during the 'Cultural Revolution'. These paintings depict a new generation raised on luxury brands, technology, Western pop culture and competitive consumerism. It is a fitting reflection of the cultural and social shifts and economic development of contemporary capitalist China.